Work in Progress (Translation)

ART and Attraction

Art and Attraction

History

Some people may feel that the Japanese sword has a long history. Although the Japanese sword is a weapon, it has also become an object of art, faith and a symbol of authority. Some people may also feel the spirit of bushido when looking at the Japanese sword, which is said to be the soul of the Samurai. In the history of Japan, Japanese swords have been carefully preserved for over a thousand years. Their historical role has been significant and even today, they still shine brilliantly as a reminder of its creation. The Japanese swords are one of the most unique Japanese cultural assets in the world. Finding the beauty in Japanese swords is finding Japanese culture.

Sugata (shape)

There may be many people who find the beauty in Japanese swords that pursues function and eliminates all kind of waste of movement. Their shape and curvature were born out of the history of their creation, according to the needs of each, and tell the story of their history and the trends and aspects of their times.

Jigane (Steel Pattern)

Many people may be attracted to the beauty and charm of Jigane. In order to satisfy the requirements for Japanese swords to be “unbreakable, unbending and sharp”, high quality Tama-hagane is forged over and over again to produce a strong, tough sword by wrapping the low-carbon content Shin-Gane (soft iron) with the high-carbon content Kawagane (hard iron).

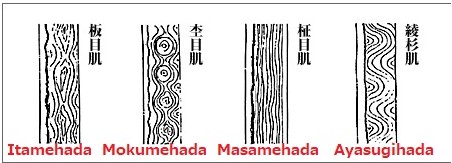

These patterns appear on the surface of Jigane, which is likened to the bark of a tree and called “Itamehada“, “Masamehada“, “Mokumehada“, “Ayasugihada” etc., and they have a variety of attractive features.

The most common type is Itame-hada, and it is often found in Sōshū-mono (swords made around current Kanagawa prefecture), which are famous for Masamune swords.

Also, small-grained Ko-itame-hada is often found in swords made by swordsmiths from Yamashiro (currently Kyoto Prefecture) in the Kamakura period, and the ones that are especially fine and tightly packed are called Nashiji-hada. And, the swords in the end of the Edo period are called Muji-hada or Kagami-hada since they are so tight and very fine-grained that it’s hard to see the grains.

The Aoe School of Bicchū (present-day Okayama Prefecture) features Mokume, and the Masame-hada is said to be the characteristic of Yamato-mono (the swords made in present Nara prefecture). Furthermore, apart from Hamon, sometimes Utsuri, a white haze like the shadow of Hamon, appears on Jigane. The Bizen swords have the most beautiful Utsuri, which is a big highlight.

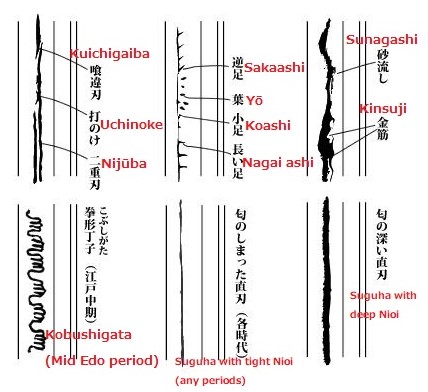

Hamon (Temper Pattern)

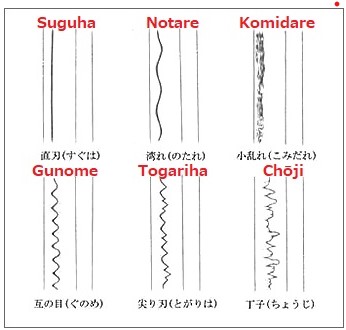

Speaking of the beauty of the Japanese swords, the beauty of “Hamon” must be mentioned along with its Sugata and Jigane. Hamon is a pattern created by quenching techniques. Clay called Yakibazuchi is applied to the blade using a spatula. Depending on how it’s applied, it can be either Suguha or Midareba or etc., and the shape of Hamon is determined. This is called Tsuchitori. When the clay of Tsuchitori is dry, put it in the furnace and then put it in the tank after checking the degree of burning of the blade. This is called Yakiire, and is said to be the most important process that requires the most skill.

The patterns of Hamon are attractive and varied, as they reflect the era in which they were created, the lineage and characteristics of the swordsmiths.

Hamon has two types such as Nie and Nioi caused by quenching. What looks like a glittering star in the autumn night sky is called Nie, and what looks like a hazy view of the Milky Way is called Nioi.* This can be said to be the sum total of the swordsmith’s aesthetic sense.

The style with a lot of Nie on the middle of the blade is called “Nie-deki“, and it is mainly found in the lineage of early Kamakura swords and Sōshū-mono swords.

The style of “Nioi-deki” is represented by Bizen-mono from mid Kamakura period and Bicchū Aoe-mono from the Nanbokucho period.

*Nie is the coarse particles that can be seen by the naked eye. Nioi is so fine that it can only be seen with a microscope.

Some Keshiki (patterns, appearance) are called “Hataraki“. For example, Nie on the blade are joined and become a thin line, and the one that appears to shine and more brightly is called Kinsuji, the one that is thicker and longer is called Inazuma. If such similar one is to seen on the base part of the blade, it’s called Chikei. If Nie has hardened in one area, it is called Tobiyaki. There are also many other interesting features, such as Ashi, Yō, Sunagashi, etc. that appear in the blade’s surface.

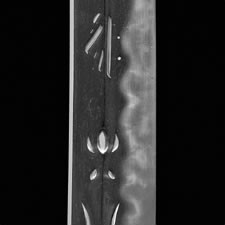

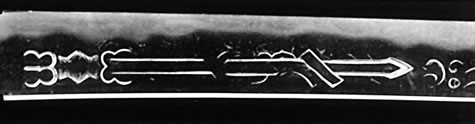

Horimono (Blade Engraving)

Engraving of blades was already practiced since the Heian period. Some are from the practical, some are from faith, some are decorative, and some are distinctive depending on the fashions and linage of the times.

In the old sword, there are many engravings that show faith in addition to grooving along the blade. There are characters such as 梵字 (Siddhaṃ script), 剣 (sword), 不動明王 (Acala), 倶利迦羅 (Kulika), 三鈷剣 (three-pronged vajra), 護摩箸 (Goma chopsticks), 八幡大菩薩 (Hachiman Daibosatsu = great Bodhisattava Hachiman), 南無妙法蓮華経 (Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō = Glory to the Dharma of the Lotus Sutra), etc.

In the era of new swords, they became more and more decorative, with carvings of 鶴亀 (cranes and turtles), 上下竜 (ascending and descending dragons), 松竹梅 (pine, bamboo and plum trees = an auspicious grouping), and more.

Sword Basics

Types and construction of swords

Japanese swords can be classified into the following types according to their shape and size.

Chokuto

Chokutō (straight sword) is a sword before Wantō (curved sword), and was produced from the Kofun period to the Nara period. It’s almost straight or slightly curved inward, and Hirazukuri or Kirihazukuri structure.

Tachi

Tachi-swords are displayed with the blade edge down when you look at them in museums, and were worn from the late Heian period (12th century) to the early Muromachi period, wearing them around the waist (i.e., hanging ). They are highly curved, and the blade length is usually about 2 Shaku 3 to 6 Sun (70 to 80 cm).

Katana

Used in place of the Tachi from the mid-Muromachi period (late 15th century) to the end of the Edo period (mid-19th century). The blade length is over 2 Shaku (60.6 cm), but slightly shorter than a Tachi. Contrary to the sword, point to the waist with the blade facing up. When a sword is shortened by doing Suriage (making shorter from the tang to change its length), it’s called a Katana, and is worn at the waist with the blade edge up.

Wakizashi

1 Shaku (30.3 cm) or more and 2 Shaku (60.6 cm) or less, and worn around the waist like a sword. There is also the one called Kowakizashi, 1 Shaku 2 to 3 Sun (36 cm to 40 cm). In the Momoyama and Edo periods, it was used as Sashizoe (held as a spare) of a sword as a set, and called Daishō (large and small).

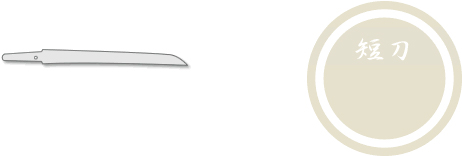

Tanto

Less than 1 Shaku (30.3 cm) in length and also called Koshigatana. The short swords before the appearance of Wantō were called Katana, also.

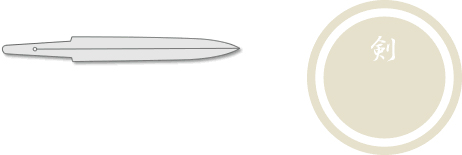

Ken/Tsurugi

A Ken/Tsurugi is the ones that have a blade on both sides with no curvature.

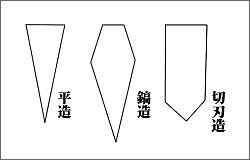

Tsukurikomi

Tsukuri-komi is a three-dimensional expression of the structure of a sword. There are various types such as Hira-zukuri (flat), Shinogi-zukuri (curved blade with Yokote and a ridge), Kiriha-zukuri (cutting edge), and Moroha-zukuri (double-edged).

Japanese Sword History

History of Japanese swords

The shifting from Chokutō (straight swords) to Wantō (curved swords) is thought to have occurred after the middle of the Heian period, and it is generally thought that it was after the Taira no Masakado and Fujiwara no Sumitomo no Ran (Jōhei/Tengyo no Ran) in the first half of the 10th century. Prior to that, swords were called Jōkotō, a continental style straight sword brought to Japan from the continent.

The Japanese swords that appeared after the middle of the Heian period changed dramatically along the battle style changing in that era, and were improved and achieved more practical effects in each battle. Also, Japanese swords were produced mainly in the five countries of Yamato, Bizen, Yamashiro, Sagami, and Mino, by master craftsmen in various areas, so since the Meiji period this had been called “Gokaden“. In the Shintō (new sword) period of the Edo period, some people who were not satisfied with this and created new techniques combined the methods they learned by themselves with other methods to create new techniques, and these techniques were passed on to the modern swords.

- Jōkotō

Jōkotō is a straight swords without warping, and mostly made of Hira-zukuri (flat blades) and Kiriha-zukuri (cutting blade). There are two types of materials about swords from this era: one excavated from ancient burial mounds and the other from the Shōsōin estate in the Nara period.

2. Late Heian period – early Kamakura period

From the late Heian period, the “warped” curved swords, the Shinogi-zukuri, that we now commonly see have appeared. These swords are generally slender and curved strongly from the Nakago (tang) to the Koshi-moto (bottom of the blade), and the top width is significantly narrower than the bottom width, making it Ko-kissaki (small tip). This is called Koshi-zori (Highest curvature lower than the center). From the middle to the top, the curve is pushed down as if pressed from the Mune (spine).

3. Mid-Kamakura period

During the Kamakura era, when the samurai were at the height of their power, the Tachi was also at it peak construction. There is little difference in width between the bottom and the top (it does not become thin even), and the curve is a Koshi-zori, but there is some warp at even from the middle to the top, and becomes the Chū-kissaki (medium tip), “Ikubi (boars neck) –fū“. The gorgeous Chōji-midare became popular Hamon (pattern) style.

4. Late Kamakura period

There are some that have a slightly extended sword, which is almost the same as the middle of the Kamakura period, and some that are slightly slender and look like those of the end of the Heian period or the beginning of the Kamakura period. Warpage is added. The blade design begins to appear as Gunome (an undulated pattern) or Notareba (a gently undulating pattern). It’s said that Gorōnyūdō Masamune from Sagami Province had perfected the style of Nie.

5. Nanboku-chō period

In this era, wide swords with a blade length of 3 Shaku (90.9 cm) were made, and short swords also became a large swinging figure. All of them were built with the thin layers to reduce the weight. In addition, more and more grooves were carved along the blade. Also, in later times (mainly during the Tensho and Keicho eras), many swords were transformed into Uchigatana (unnamed swords) by becoming O-suriage (swords that were shortened from the Nakago).

6. Early Muromachi period

In the early Muromachi period, the swords shows a style which resembles the style of the early Kamakura period. The blade length is 2 Shaku, 4 or 5 Sun (72.7 cm to 75.8 cm), and the body width is a little narrow, and it’s warped. At first glance, it looks like it was from the Kamakura period, but it ihas a characterized style by a slight warp.

7. Late Muromachi period

In the late Muromachi period, the battle style became a group battle on foot, and battling swords with the blade up and worn inside the waistband became more common. After the Onin and Bunmei civilization wars, warfares broke out in many places, and Kazu-uchimono (ready-made products) appeared on the market. In particular, the ones which have been carefully trained by ordering are distinguished and called Chūmon-uchi. Bizen (Okayama Prefecture) and Mino (Gifu Prefecture) are the two major production areas. The size of the sword became shorter, and most of them are about 2 Shaku 1 Sun (63.6 cm) and have a strong tip warp. Also, the Nakago (tang) is made short, so that it is suitable for one-handed striking.

8. Azuchi-Momoyama period

In the history of swords, those before the Keichō (1596-1614) era are called Kotō (old swords), and those after that are called Shintō (new swords). In the Azuchi and Momoyama period, swordsmiths gathered around the castle towns of the new feudal lords, including Kyoto and Edo. And the development of transportation facilitated the exchange of iron materials, and foreign-made iron, namely nanban iron, was also used. The appearance of the swords is very similar to the shape of Ōsuriage from the Nanboku-chō period. Some have a wide body width with extended Chū-kissaki (medium tip) and some have Ōkissaki (large spearhead), and the layers are thicker. Most of the blade lengths are around 2 Shaku 4 Sun and 5 Sun (72.7 cm to 75.8 cm).

9. Edo period (early period)

The shape of swords from the early Edo period has narrower top width than the bottom width, and the warp is noticeably shallower, and it has Chukissaki, namely the shape of Gokoro. Most blades length is around 2 Shaku 3 Sun (69.7 cm). This unique shape was made especially during the Kanbun and Enpo years, so it’s called the Kanbun Shintō.

10. Edo period (Genroku period)

This was mainly during the Teikyo and Genroku eras, a transitional period from the Kanbun Shintō to the Shinshintō. The world was at peace, and innovative and splendid Hamon appeared. The curve is a little deeper than the Kanbun Shintō.

11. Bakumatsu period (Late Tokugawa Shogunate period)

Those after Bunka and Bunsei eras are called Shinshintō. The body shape is wide, with little flare in the bottom and top width, and it’s long (2 Shaku 5 or 6 Sun) with a shallow curve, and a thick layered, majestic build. Suishinshi Masahide and Nankai Tarō Tomotaka advocated the restoration of old swords, and Taikei Naotane is one of the students of Suishinshi. Minamoto Kiyomaro also aspired to restore the style of Sōshūden, and his skill was highly regarded.

12. Since the Meiji era

Swords from the Haitō Edict (Sword Abolishment Edict) in 1876 to the present are called Gendaitō (modern swords). The swordsmiths lost their jobs when the Haitō Edict was issued, but in 1906, Gassan Sadatoshi and Miyamoto Kanenori were appointed as imperial artisans and their swordsmithing skills were protected. From the Meiji, Taishō, Shōwa, Heisei eras, the forging technique have been carried on to today. Modern swords, regardless old or new, are copied from the styles of famous sword craftsmem of all periods, especially from the Kamakura period.

Sword Making Process

Sword making process

As the name implies, Japanese sword is unique to Japan, and is ranked as one of the world’s finest ironworks. In order to fulfill the requirements of the Japanese sword as a weapon, ingenuity and effort have been put into its production.

Material of Japanese sword

The material for Japanese swords is made using Tatara, an ancient Japanese iron manufacturing technique. The iron produced using this Tatara in the broadest sense of the word is a mass called Kera, which is made up of three different types of steels. These are crushed and sorted, and classified according to their carbon content as follows.

Tetsu (Iron) in a narrow sense … Carbon content 0.0-0.03%. Can be stretched without heating, if you hit it.

Hagane (Steel) ・ ・ ・ Carbon content 0.03 to 1.7%. Can be stretched if you heat and hit it.

Zuku (Pig iron) ・ ・ ・ Carbon content of 1.7% or more. Cannot be stretched no matter you heat or what you do.

“Tamahagane” is a type of steels, which are classified as “Hagane“, with a particularly good and homogeneous fracture surface, and is used as a material for swords.

On the other hand, pig iron contains a large amount of carbon, so the carbon is removed (decarburization), while iron, on the other hand, absorbs carbon (absorption of carbon) and is used to adjust to the carbon content of Hagane.

Japanese sword production process

The process of making a Japanese sword differs slightly depending on the time periods, schools, and individuals, but here the general making process using Tamahagane will be explained.

1. Mizuheshi, Kowari

Heat Tamahagane and hammer it out to a thickness of about 5 mm (Mizuheshi), then crush it into 2 to 2.5 cm square pieces (Kowari), and select 3 to 4 kg of good quality parts out of the pieces, and use it as a direct material.

2. Tsumiwakashi

Pile up the small pieces of material on a Teko (fulcrum) and heat them in a Hodo (furnace). In this process, the material is sufficiently boiled (= heated) to form a lump.

3. Tanren / Kawagane making

Tanren is performed to adjust the carbon content and remove impurities. The method of Tanren: Strech the fully-heated material out flat, and then fold to stack it on top of each other. This work is repeated about 15 times. Especially, the first half of this process is called Shitagitae, and the second half Agegitae.

By Tanren, Kawagane (= hard iron that wraps soft core iron) is made. As a result of about 15 times of Tanren, the squared calculation yields about 33,000 layers. This is one of the reasons why Japanese swords are very tough.

4. Shinganezukuri, combining

Around the same time making softer iron, make Kawagane. Japanese sword pursues three conditions: it doesn’t break, it doesn’t bend, and it cuts well. However, in order to cut well and not to bend, the steel has to be hard. On the other hand, the steel has to be soft in order not to break.

The solution to this contradiction is the process to wrap a soft Shingane iron which has low carbon content with a hard Kawagane iron which has high carbon content. This is a major feature of Japanese sword production.

There are many types of wrapping methods, such as Kōbuse, Honsanmai, and Shihōzume. This varies depending on the era, school, and individuals.

5. Sunobe / Hizukuri

When the combining of Kawagane and Shingane is done, it is heated and hammered out to a flat rod. This is called Sunobe.

When Sunobe is done, tap it with a small gavel to shape it according to the manners of making a Japanese sword, and then use Sensuki (grinding tool) to prepare Nikuoki (thickness toward the rim of a Tsuba). This is called Hizukuri.

6. Tsuchioki (Tsuchitori) / Yakiire

Make Yakibatsuchi with fire-resistant clay mixed with fine powder of charcoal and fine powder of grindstone. Proceed Tsuchinuri (scraping the clay off to form various hamon patterns in tempering) according to the type of Hamon (temper pattern along blade edge). Apply the clay thinly on the part to be baked, on the other part thickly, and heat thin to about 800 degrees and then cool rapidly in time.

7. Shiage (Finishing) / Meikiri (engraving a name)

After Yakiire (quenching), correct bends and warps, and rough grind.

Finally, check there are no scratches or cracks on the blade, file the center (Nakago), make Mekugiana (hole for sword peg), and lastly add the craftsman’s name

.

The Japanese sword, which is required as a weapon to be “unbreakable, unbending and sharp” which is contradictory, has been fullfilled and made into an each single blade with variety of innovations. And the beauty born from such practical use is the charm of Japanese sword. Also, even today, when Japanese swords are used no longer as weapons, as long as they are traditional crafts, this production process should be faithfully followed.

Sword Polishing

Polishing of Japanese sword

The polishing techniques for polishing Japanese swords have made great progress along with the perfection of the swords. Professional polishers were already known to have existed during the era of Emperor Toba. Even after this, the polishing techniques were refined. In the Meiji period, Honami Heijuro Narishige, a master sword craftsman, appeared on the scene. He added his aesthetic sense to the advanced traditional techniques, and the art sword polishing techniques that we see today was established.

The goal of the polishing work is to bring out the beauty of the Japanese sword such as the unique curvilinear beauty of the Japanese sword, tough Jigane, and splendid Hamon, and the grace and dignity of Japanese swords.

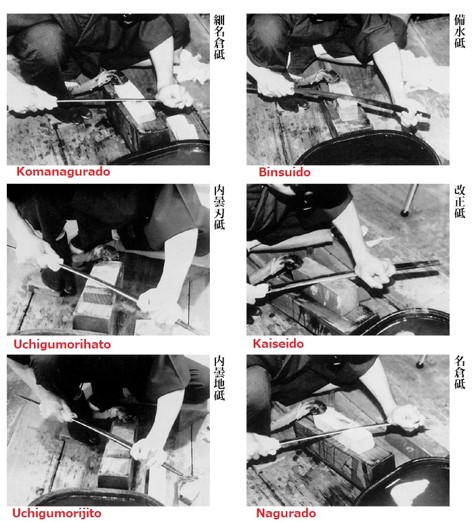

1. Shitaji togi

Polishing Japanese swords can be broadly categolized into Shitaji togi (base sharpening) and Shiage togi (finishing sharpening).

Shitaji togi meas the basic work of shaping a sword, and usually six types of whetstones are used. The types of whetstones are arranged in order of grit size as follows.

・ Iyodo ・ ・ ・Produced from Matsuyama, Ehime Prefecture. About 400 Ban ( “Ban” indicates the grit size)

・ Binsuido ・ ・ ・Produced from Amakusa, Kumamoto Prefecture. About 400 Ban

・ Kaiseido ・ ・ ・Produced from Yamagata Prefecture. About 600 Ban

・ Nagurado ・ ・ ・Produced from Minamishitara District, Aichi Prefecture. About 800 to 1200 Ban

・ Komanagurado ・ ・ ・The same place of origin as Nagura. About 1500 to 2000 Ban

・ Uchigumorido ・ ・ ・ There are two types of Uchimogurido such as Uchimoguri hato whose blade part is sharpened, and Uchimoguri whose ground part is sharpened. Both produced from Kyoto, about 4000 to 6000 Ban.

2. Shiage togi (final polishing)

After finishing Shitaji togi, the next step is Shiage togi. There are two different ways, Hazuyado and Jizuyado. The first one sharpens Hamon, and the second one sharpens the ground part. Hazuyado scrapes high quality Uchigumorido thin and small, and line Yoshino paper with glue or lacquer on the back.

Jizuyado uses thin divided Narutakido, but depending on the school, it’s crushed into 1 mm squares with fingertips, and this is called Kudaki jizuya.

3. Nugui

After finishing Shiage togi, the next step is Nugui. Nugui is a method to give a luster to the blade, and usually a method called Kanahada nugui is used. This is a method in which iron oxide produced during Japanese sword Tanren is burned for a long time, finely powdered, mixed with Chōji oil, and then polished with Yoshino paper.

4. Hadori

The next step is Hadori. Hadori is the process of finishing the blade part white and beautifully. The whetstone used for this process is Hazuyado, which is ground with the abrasive water of Uchigumorido according to the shape of Hamon. This work is also discribed as “Ha wo hirou (= picking up the blade).”

5. Migaki

After Hadori, the next step is Migaki (polishing). Migaki means polishing the Mune (back ridge of sword blade), namely Shinogiji (sword flat between the mune and ridgeline of the blade) using the iron rod with a length of about 15 cm. The unique black luster is created by this work.

6. Narume

Almost the final process is the “narume” of Bōshi (temper line in kissaki). Narume is the process of polishing Bōshi, which begins with determining (= finishing) Yokotesuji (horizontal lines). Once Yokotesuji is finished, sharpen Bōshi up using the Narume stand with the best quality Hazuya paper during being careful not to damage the Yokotesuji.

7. Keshō togi

Polishing, which has gone through a long process, is finally finished with Keshōtogi. Among them, “Keshō migaki” is the signature of the Togishi (polisher), so to speak, and means to polish several lines in the Mune of Bōshi using a polishing rod.

Here explained is, how to make a Japanese sword, especially about Tanren and Kenma. However, in order to complete one Japanese sword, the technique of many masters such as Sayashi, Nuri, Tsukamakishi, Shiroganeshi, and Chōkinshi. Craftsmanship is required. You can say the major feature of Japanese sword production is that a sword can be completed only when all these techniques are combined.

Sword Care and Cleaning

JAPANESE SWORD CARE AND ETIQUETTE

Japanese swords are rightfully famous for their awesome cutting power; they are also easily damaged. The fine polish of the sword, especially, is very fragile. It is our responsibility as temporary owners of these artistic and historic artifacts to see that they pass onto future generations of collectors. Towards that end the NBTHK American Branch presents this primer on sword care and etiquette.

SWORD CARE TOOLS

A small brass hammer, mekugi nuki, is used to remove the pin (mekugi) from the sword’s handle. Choji oil, specially made for swords, is used to protect the sword from rust. Uchiko is a fine powder contained in an inner wrapper of paper and an outer wrapper of silk, used to clean oil from the sword. The paper and silk serve as a filter to allow only the finest uchiko particles onto the blade. There are different grades of uchiko; only the best should be used on blades in polish and the uchiko ball used on blades in polish shouldn’t be used on blades with any rust. Nugui gami (sword paper) is used to wipe uchiko and oil from the blade. This should be thoroughly crumpled before use to remove any coarse fibers.

Clean, unscented, white facial tissue that hasn’t been made from recycled fibers can be used in place of the nugui gami.

EVERYDAY SWORD CARE

When a sword isn’t being viewed it should be enclosed in a sword bag, which will prevent the blade from coming loose in or falling out of the scabbard. Japanese swords are best stored horizontal and in a dry environment (not a damp basement).

When carrying a mounted sword, whether in Samurai mounts or plain wooden mounts (shira-saya) always keep the handle higher than the scabbard. At all times, when the sword is mounted, it must have the pin (mekugi) through the hole in the handle and tang of the sword. Without the mekugi the blade can move inside the scabbard and become chipped or scratched. manners and ca

Never touch the polished portion of the blade; the slightly corrosive sweat of your fingers can etch fingerprints onto the blade’s surface. Never touch the polished part of the sword to your clothing. To do so is considered bad manners and can damage the polish.

Unsheathing the Sword:

Grasp the scabbard (saya) near its mouth from below with your left hand. Grasp the handle (tsuka) from above with your right hand. With the sword held horizontally and pointing away from you, edge facing the ceiling, gently withdraw the blade from the scabbard. Edge to the ceiling allows the blade to ride on its back (mune) and lessens the chance of scratching the polish or chipping the edge. Don’t stop part way to examine the blade, as this also can damage the edge. When the blade is almost completely withdrawn, lower the far end of the scabbard a bit and finish.

Removing the Handle:

First the pin (mekugi) must be removed. Determine which end of the mekugi is smaller and gently push on this end with the mekugi hammer. Mekugi are easily lost so keep track of where it is when out of the handle. Hold the bottom of the handle in your left fist, with the blade angled up past your right shoulder and the edge pointing away from you. Strike the top of your left fist with your right fist, gently at first blow and with added force on subsequent blows until the sword comes loose in the handle. Once loose, a few gentle taps on your fist should advance the blade enough for you to get your fingers on the tang (nakago) and lift the sword from the handle. If the sword isn’t loose don’t try to force it; a few more taps on your fist are in order. Force applied at the habaki can damage the habaki or chip the beginning of the sword’s edge (hamachi).

One note of caution: tanto and short wakizashi can have small nakagos. Be very gentle with the first blow on your fist, or the blade might go flying.

Once free of the handle you can slide the tsuba and washers (seppa) off the tang. To remove the habaki grasp it by its sides and pull down gently.

Examining the Sword:

With the nakago in one hand you can rest the upper portion of the sword on a soft, clean cloth or sword paper in your other hand. As you examine the sword, be aware of your surroundings. You don’t want to bump into a lamp or person or put the blade into the ceiling.

Reassembling the Sword:

Slide the habaki onto the tang and replace the tsuba and washers in their original order.

Hold the handle vertical and lower the nakago of the sword into the handle. Maintain the sword in the vertical position and tap on the bottom of the handle with the heal of your free hand. A few taps should be sufficient to firmly seat the nakago in the handle. Replace the mekugi through the hole in the handle.

Replacing the blade in the scabbard is a reverse of the removal process. With the scabbard held in your left hand, far end slightly lowered, lay the back of the sword tip in the mouth of the scabbard, edge to the ceiling. As you gently slide the blade in, raise the far end of the scabbard until you feel it to be in the right plane. Continue until the habaki seats in the mouth of the scabbard.

Passing a Sword from Person to Person:

If the sword is in its mounts the passer holds the sword horizontal with the edge facing himself, one hand at the end of the handle and the other towards the other end of the scabbard. The receiver places one hand on the handle and the other on the scabbard and acknowledges control before the pass is made. If the blade is bare or mounted in the handle only, the passer grasps the blade either at the top of the handle or the top of the nakago (but below the polish). The blade should be vertical, and the edge should face the passer. The receiver grasps the nakago or handle below the passer’s hand, acknowledges control, and takes the sword.

Note: always during the pass the edge of the sword faces the person passing. It is considered bad manners to pass a sword with the edge facing the recipient.

Oiling the Sword:

When the sword isn’t being viewed it should be protected with a very fine coat of Choji oil. The 1st few months after a sword is polished, due to latent water from the polishing process, is a time when the oil coat is especially important.

Place 2 or 3 drops of the oil on a clean piece of tissue. Remove all the mounts from the sword. With the paper folded over the back of the blade, starting an inch above the nakago, gently wipe up the blade to the tip. You don’t want to start at the top of the nakago because doing so risks dragging rust particles from the nakago over the sword’s polish. This last inch at the bottom of the sword is wiped downward to the nakago after the rest of the blade has been oiled. At this point the polished part of the sword is coated in oil, probably too much.

Take a clean piece of tissue or crumpled sword paper and gently wipe the oil off the sword. The tiny amount of oil that is left on the blade is sufficient to protect it. If too much oil is left on the sword it can collect inside the scabbard and create a gummy mess.

Cleaning Oil from the Sword:

In order to clearly see the grain and temper of a Japanese sword, the oil must be removed. Begin by wiping with a clean tissue, from an inch above the nakago up to the point and then that last inch down to the nakago. Hold the blade in your left hand with the edge facing away from you and strike the back (mune) of the blade with the uchiko ball. Half dozen strikes with the ball over the length of the mune should be sufficient. Sometimes the uchiko ball can let loose coarse particles that could scratch the polish. If you strike the mune these particles will fly by the blade and only fine particles will settle.

With the sword paper or clean tissue wrapped around the back of the blade gently wipe as before, up to the point and down to the nakago. Be careful not to exert heavy pressure and never go back and forth over a particular spot; gentle, continuous strokes are called for.

Sword Terminology

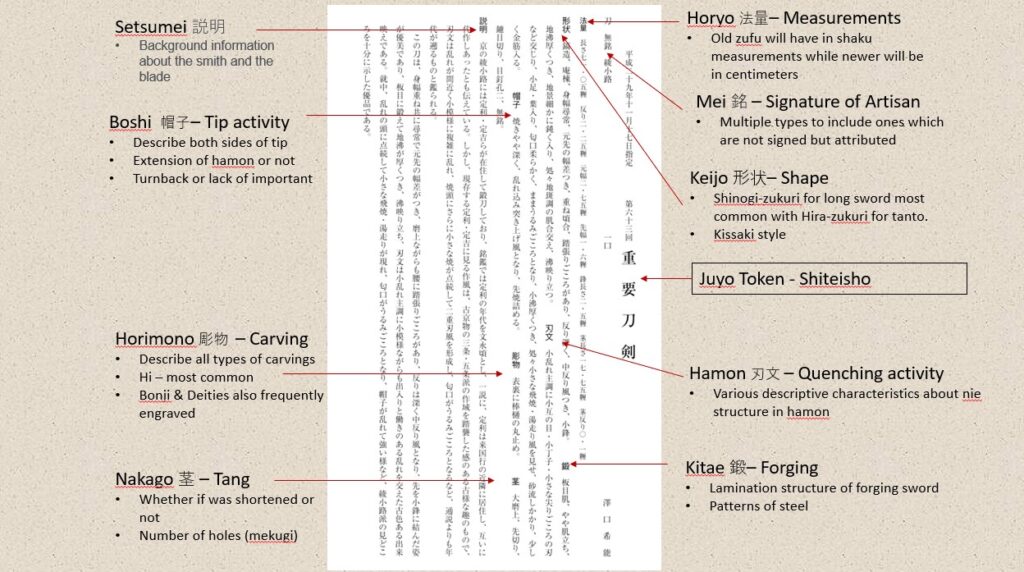

Papers and Terminology

Keijo – 形状

| Romanji | Kanji | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Chisakatana | 小さ刀 | short katana |

| Chokoto | 直刀 | prehistoric straight swords |

| Chukan-sori | 中間反り | deepest point in sori is in the middle |

| Chu-sori | 中反り | medium sori |

| Daito | 大刀 | long sword (over 24 inches) |

| Fukura Kareru | 脹枯れる | the fukura is rather flat, and not fully rounded |

| Fukuro Yari | 袋槍 | socket yari |

| Funbari | 踏ん張り | blade is noticeably wider at the base than at the tip |

| Habaki Moto | section of the blade for about three inches above the habaki | |

| Hagire | 刃切れ | perpundicular cracks in the edge of hamon (fatal flaw) |

| Haki omote | 佩表 | the side facing out when the sword is slung ha down, as with a tachi |

| Haki ura | 佩裏 | the side facing in when the sword is slung ha down, as with a tachi |

| Han | 藩 | a feudal clan |

| Hira zukuri | 平造 | blade without a shinogi (flat blade) |

| Hira niku | 平肉 | hira niku is flat |

| Hira niku oi | 平肉多い | hira niku is curved or full |

| Hira niku Sukunai | 平肉少ない | hira niku is flat |

| Hon zukuri | 本造 | shinogi-zukuri |

| Ihori Mune | 庵棟 | peaked back ridge |

| Ikubi | 猪首 | ikubi kissaki – stout, resembling a boar’s neck with a straight edge |

| Jumonji | 十文字 | cross shaped |

| Kakemono | 角留 | square stop on a groove |

| Kasagi-Sori | 笠木反 | same as chukan sori or torii sori |

| Kasane | 重ね | thickness of blade |

| Kasane Usui | 重ね薄い | thin kasane |

| Katakiriba | 片切り刃 | blades sharpened on one side only |

| Katakiri-bori | 片切り彫 | groove engraved with a flat border |

| Katana | 刀 | sword worn in the obi, cutting edge up |

| Katana Hi | 刀樋 | groove that is shaped like a katana |

| Katana Mei | 刀銘 | sword worn with the edge up, the mei is on the side facing outward |

| Ken | 剣 | straight double edged sword |

| Kitae | 鍛え | structure of the blade and the manner of forging |

| Kodachi | 小太刀 | small tachi |

| Koshi | 腰 | the area a few inches above the machi |

| Koshi-zori | 腰反り | sori is towards the bottom |

| Machimune | 関棟 | back edge of the machi, which are unlikely to have rust re-applied in the event of tampering with the nakago |

| Maru Mune | 丸棟 | round mune |

| Maru Dome | 丸留 | round stop on a groove |

| Mihaba | 身幅 | width of sword blade at the machi |

| Mitsu Mune | 三つ棟 | three |

| Mono Uchi | 文字 | the section of the blade about six inches below the tip |

| Moroha | 諸刃 | double edged |

| Moto | 元 | base |

| Moto Choji | 元丁子 | choji ha at the base |

| Moto Haba | 元幅 | blade width near habaki |

| Moto Kasane | 元重 | blade thickness near habaki |

| Moto uchi | 元打ち | area of the ha near the base |

| Motte | 以って | means “made by” or “made with” |

| Mune | 棟 | back ridge of sword blade |

| Mune machi | 棟区 | notch at start of mune |

| Munezuru | 棟蔓 | a very long return on the boshi, like mune yaki |

| Musori | 無反り | no sori |

| Nagamaki | 長巻 | halberd weapon mounted as a sword |

| Nagasa | 長さ | blade length (from tip of kissaki to munemachi) |

| Naginata | 薙刀 | halberd |

| Naginata Naoshi | 薙刀直し | sword made by grinding down a naginata in this case, the boshi is frequently yakizume |

| Niku | 肉 | meat (blade having lots of fullness) |

| Osoraku Zukuri | 恐らく造り | tanto form in which the yokote is at about the middle of the blade |

| Saki | 先 | tip, front, or end |

| SAKI ZORI | 先反り | curvature in the top third of the blade |

| Saki sori | 先反り | the highest part of the sori is towards the saki |

| Shinae | 撓え | ripples in steel due to bending of blade |

| Shingane | 心鉄 | core steel |

| Shinogi | 鎬 | ridgeline of the blade |

| Shinogi Ji | 鎬地 | sword flat between the mune and shinogi |

| Shinogi Suji | 鎬筋 | shinogi line |

| Shinogi zukuri | 鎬造 | made with a shinogi, as opposed to a flat, or hirazukuri blade |

| Shobu zukuri | 菖蒲造 | blade construction in which the blade resembles the iris leaf in shape |

| Soebi | 添樋 | additional hi alongside main hi which is smaller that the main hi |

| Sori | 反り | curvature |

| Sugata | 姿 | form, body implies more than just shape, overall appearance |

| Sun-nobi | 寸延び | longer than normal |

| Sun-zumari | 寸詰まり | slightly shorter than normal |

| Tachi | 太刀 | long swords which were slung at the waist with the edge down |

| Takai | 高い | high |

| Tamahagane | 玉鋼 | raw steel for making swords |

| Tanto | 短刀 | blade less than 12 inches |

| Torii zori | 鳥居反り | sword curve in the middle of the blade |

| Tsukuri/ zukuri | 造込 | sword |

| Tsukuri komi | 造込み | generally speaking, the overall construction of the swords in regard to shape |

| Uchigatana | 打ち刀 | two handed katana |

| Wakizashi | 脇指 | short sword (blade between 12 and 24 inches) |

| Yanone | 矢の根 | arrowhead |

| Yari | 槍 | spear |

| Yokote | 横手 | line separating the point from the rest of the blade |

| Zukuri | 造り | sword |

Kitae – 鍛 Forging, Jihada – 地肌 Patterns in Steel, Jigane 地鉄 Surface Steel (Both part of Kitae – 鍛)

| Romanji | Kanji | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Are | 荒れ | coarse or rough |

| Ayasugi Hada | 綾杉肌 | a wavy grain especially used by gassan and satsuma naminohira smiths |

| Bo utsuri | 棒映り | straight utsuri |

| Chikei | 地影 | dark lines that appear in the ji similar to kinsuji or inazuma |

| Dan utsuri | 段映り | two types of utsuri seen on a sword |

| Fukure | 脹れ | flaw; usually a blister in the steel |

| Hada | 肌 | grain in steel, pattern of folding the steel |

| Hada Arai | 肌荒い | rough grain of the hada |

| Hadame | 肌目 | grain |

| Hada mono | 肌物 | pattern in the hada, but even more outstanding |

| Hada tachi | 肌立ち | grain in the hada stands out, looking like the raised grain in a piece of wood, but it is not actually raised |

| Hagane | 鋼 | steel |

| Hikari | 光 | light reflections |

| Itame | 板目 | wood grain pattern in the surface steel |

| Itame Nagareru | 板目流れる | hada of itame kitae is flowing (nagareru) with a hint of masame, |

| Itame Tachi | 板目立ち | distinct itame pattern having a raised look |

| Itame Tsumi | 板目詰み | tight itame pattern |

| Ji | 地 | it can be seen from context whether this refers to the ji 地 of the blade or tsuba or is the common term 字 |

| Jigane | 地鉄 | surface steel |

| Ji hada | 地肌 | surface pattern of the hada |

| Ji nie | 地沸え | islands of nie in the ji |

| Jiba | 地刃 | abbreviated term meaning both the ji 地 and the ha 刃 |

| Jifu | 地斑 | black speckling resembling utsuri in the ji |

| Jitetsu | 地鉄 | steel of the ji |

| Katai | 堅い | tight or hard |

| Kawagane | 皮鉄 | skin or surface steel |

| Kobuse | 甲伏せ | construction in which soft steel is covered by hard steel |

| Konuka Hada | 小糠肌 | hada with a grainy appearance like rice bran and rice germ produced in milling rice, typically used to describe Hizen |

| Masa | 柾 | used as short for masame |

| Masame | 柾目 | straight grain pattern in the steel on the surface of the blade |

| Masame Nagareru | 正目流れる | when the entire hada of masame kitae is flowing (nagareru), this is called masame nagareru |

| Matsukawa Hada | 松皮肌 | hada resembling pine bark |

| Mokume | 杢目 | burl wood grain hada |

| Mokutachi | 杢立ち | mokume which stands out with a raised look this is an abbreviated way |

| Mujitetsu | 無地鉄 | no grain in the ji |

| Muku Kitae | 無垢鍛え | made of one kind of steel |

| Nagare | 流れ | flowing |

| Nashiji Hada | 梨地肌 | hada which resembles pear skin in appearance |

| O-hada | 大肌 | hada with large and loose grain structure |

| Ryutachi | 粒立ち | grains stand out ryu 粒 means grains, as in sand |

| Satetsu | 砂鉄 | sand iron, iron made from black sand |

| SHIMARI | 締まり | generally means tight or restricted nioi shimari means a narrow nioi line |

| Shimi | 染み | the color of the steel fading, usually due to over polishing |

| Shirakke Utsuri | 白け移り | utsuri which has faint whitish or cloudy appearance |

| Sumi | 澄 | small black splotches |

| Tachi | 立ち | literal meaning is “stand up ” |

| Tansotetsu | 炭素鉄 | carbon steel |

| Tsuru | 蔓 | vine |

| Uruoi | 潤い | watery looking |

| Utsuri 1 | 移り | “reflections” in the ji these may or may not be the same as the hamon |

| Utsuri 2 | 映り | reflection of temper line in ji |

| Uzumaki | 渦巻き | swirl, like the patterns in burl wood |

| Ware | 割れ | opening in the steel |

| Yotetsu | 洋鉄 | western steel |

| Yowai | 弱い | weak or less than |

| Yubashiri | 湯走り | concentrated nie in sections of the ji |

| Zanguri | ざんぐ | coarse pear skin-like hada |

Hamon 刃文

| Romanji | Kanji | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Ara nie | 荒沸 | coarse nie |

| Ashi | 足 | legs (lines of nioi pointing down toward the edge) |

| Ashi iri | 足入り | ashi inserted |

| Ashinaga choji | 足長丁子 | choji with long ashi |

| Choji | 丁子 | clove-like hamon pattern |

| Choji midare | 丁子乱れ | irregular choji hamon (temper line) |

| Chu suguha | 中直刃 | straight, medium width temper line |

| Deki | 出来 | a generic term meaning “contruction in style of” |

| Fuji no hana nie | 藤の花沸 | nie that is clumped nie |

| Fukai | 深い | generally means deep or wide |

| Fukame | 深め | to be made thick, as in nioi or nie |

| Fukura | 脹 | cutting edge from the yokote line to the kissaki |

| Fukuro | 袋 | bag sometimes elements of the hamon are bag-shaped, and this is referred to as fukuro |

| Fushi | 節 | pointed knot-like breaks in suguba |

| Gunome | 五の目 | half round patterns in the hamon |

| Gunome midare | 五の目乱れ | irregular gunome |

| Gunome Tsuranaku | 五の目連らなく | the gunome is not continuous, and is broken up in sections |

| Gunome Tsure | 五の目連れ | the gunome is continuous, instead of being broken up in sections |

| Ha 1 | 派 | group or school |

| Ha 2 | 刃 | hardened edge of the blade, the cutting edge |

| Ha Shizumi | 刃沈む | indistinct hamon |

| Habuchi | 刃縁 | border between the ji and the yakiba |

| Habuchi Hotsure | 刃縁ほつれ | stray lines between the ji and the yakiba |

| Habuchi Shimari | 刃縁締まり | very fine habuchi |

| Hadaka Nie | 裸沸 | nie which has a black luster |

| Hahaba | 刃幅 | width of the hamon see also yakihaba |

| Hako ha | 箱刃 | box-like hamon |

| Hako midare | 箱乱 | irregular boxlike hamon |

| Hamachi | 刃区 | notch at the beginning of the cutting edge |

| Hamon | 刃文 | temper pattern along blade edge |

| Ha saki | 刃先 | the edge of the blade |

| Hataraki | 働き | activities within the hamon or temperline |

| Hira | 平 | area extending from the shinogi to the ha or cutting edge |

| Hiro suguha | 広直刃 | wide, straight temper line |

| Hitatsura | 皆焼 | full temper |

| Hososuguba | 細直刃 | narrow suguba |

| Hotsure | ほつれ | stray lines along the hamon |

| Inazuma | 稲妻 | lightning short jagged streaks of kinsuji |

| Iri | 入り | added to, means in or insert |

| Ito sugu | 糸直 | thin, thread like hamon |

| Juka choji | 重化丁子 | double choji, often overlapping |

| Juzu ha | 数珠刃 | hamon shaped like a monk’s prayer beads also, juzuba |

| KAKUBARI Gunome | 角張り五の目 | squarish gunome see hako ha |

| Kakubari Sahagokoro | 角張り逆心 | squarish, with a slight angularity |

| KaniNo Tsume | 蟹の爪 | hamon pattern which resembles a crab claw |

| Kashira | 頭 | the heads of the choji , or the cap on the tsuka |

| Kasudatsu | 粕立つ | a condition of the nie in the hamon(light reflections) |

| Kata Ikari | 肩怒 | square shouldered |

| Kataouchi Gunome | 肩落ち五の目 | sawtooth shaped hamon |

| Kawazunoko Choji | 蛙の子丁子 | choji which looks like tadpoles also called kawazuko |

| Kikusui a | 菊水刃 | hamon which has an appearance of flowers floating on a stream sometimes requires a bit of imagination to see |

| Kinsuji | 金筋 | whitish line along hamon |

| Ko-ashi | 小足 | little ashi |

| Kobushigata | 拳形 | fist-like refers to a hamon in which the valleys of the choji are clustered like knuckle bones |

| Ko-Gunome choji | 小五の目 | small gonome with choji |

| Koi | 厚い | thick can also be read atsui, |

| Ko-midare | 小乱れ | small irregularities, no consistent pattern |

| Koshi no hiraita gunome | 腰の開いた | slope between the peaks and valleys of the hamon is long |

| Koshiba | 腰刃 | hamon in the area a few inches above the ha machi |

| Kuichigai Ha | 喰い違い刃 | hamon line is broken in crisscross lines of nie and nioi nibbled away |

| Kusamura Nie | 叢沸 | nie clustered together |

| Kuzure | 崩れ | breaking up, such as an interrupted yakiba |

| Majiri | 交じり | mixed in, usually used in combination of two hataraki |

| Marumi | 丸み | a touch of roundness |

| Midare | 乱 | irregular |

| Midareba | 乱刃 | irregular ha |

| Mimigata | 耳形 | ear shaped hamon |

| Mizukage | 水影 | hazy line in ji commonly due to re |

| Mune Yaki | 棟焼 | the mune is tempered (yaki) |

| Nezumi ashi | 鼠足 | rat’s feet small numerous ashi |

| Nie | 沸え | bleft crystals in hamon or ji |

| Nie Deki | 沸出来 | hamon that is composed principally of nie |

| NieFukai, Fukaku | 沸深い or 沸深く | thick nie line on the hamon |

| Nijuba | 二重刃 | double hamon |

| Nioi Deki | 匂出来 | hamon that is prinicipally composed of nioi |

| Nioi Fukaku | 匂深く | wide nioi line in the hamon also written nioi fukai 匂深い |

| Nioi Saeru | 匂冴える | nioi line is clear |

| Nioi SHIMARI | 匂絞まり | very fine nioi line |

| Nioi Shimaru | 匂絞まる | see nioi shimari |

| Nioi Shizumu | 匂沈む | nioi line is indistinct shizumu means to sink |

| Nioiguchi | 匂口 | the part of the nioi line next to the ji |

| Nioiguchi shimari | 匂口絞まり | very fine nioi line |

| Notare | 湾れ | wave like hamon, gradual undulations |

| Notare Midare | 湾れ乱れ | irregular wave like hamon |

| O Midare | 大乱れ | large irregular hamon |

| O-Choji | 大丁子 | large choji |

| Saeru | 冴える | clear and distinct – usually referring to nioi |

| Saka | 逆 | slanted |

| Saka ashi | 逆足 | ashi slanted toward the saki or tip of the blade |

| Saka choji | 逆丁子 | choji slanted toward the saki or tip of the blade |

| Samishii | 寂しい | sparse additional features showing in the hamon |

| Sanbonsugi | 三本杉 | “three cedars” (hamon with repeating three peaks) |

| Shirajimi | 白染み | whitishness that appears in the ha also pronouonced shirojimi |

| Sudareba | 簾刃 | rattan blind shaped lines along the hamon |

| Sugu Yakidashi | 直焼出 | suguba for the first inch or so up from the hamachi |

| Suguba | 直刃 | straight hamon |

| Sunagashi | 砂流し | literally, flowing sand pattern |

| Tamayaki | 玉焼き | in hamon which tend to midare, tama, or round spots, occur in the ji also, hamon in which the kashira are round |

| Tani | 谷 | valley |

| Tatsu | 立つ | to stand up or to stand out |

| Tobiyaki | 飛焼 | islands of tempering in the ji |

| Togari ha | 尖り刃 | sharp pointed patterns in the ha |

| Toranba | 濤瀾刃 | high wave like hamon |

| Tsume | 爪 | claw |

| Tsuno Yakiba | 角焼き刃 | the kashira of the yakiba look like steer horns peculiar to fujishima |

| Tsure | 連れ | connected or cotinuous |

| Uchinoke | 打ちのけ | small moon shaped patterns of nie in the hamon |

| Urumi-Gokoro | 潤み心 | watery looking hamon misty see also ha shizumu |

| Yahazu | 矢筈 | hamon pattern resembling arrow notches |

| Yakemi | 焼け身 | burned sword |

| Yaki Ire | 焼入れ | fast quenching of sword (tempering) |

| Yaki Kukure | 焼崩れ | breaks in hamon |

| Yaki otoshi | 焼き落と | hamon runs out into the ha saki an inch or so before the ha machi |

| Yakiba | 焼き刃 | hardened, tempered sword edge |

| Yakidashi | 焼出し | portion of hamon two or three inches above the base |

| Yakigashira | 焼き頭 | heads on the hamon pattern on the ji side of the hamon |

| Yakiba | 焼き幅 | width of the tempered portion |

| Yakikomi | 焼き込み | the hamon of the yakidashi goes in toward the shinogi |

| Yo | 葉 | small patterns in the hamon which look like leaves |

| Zumi | 積み | piled up or packed tightly “tsumi” becomes “zumi” |

Boshi 帽子

| Romanji | Kanji | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Boshi | 帽子 | temper line in kissaki (point) |

| Chu-kissaki | 中切先 | medium sized point (kissaki) |

| Hakikake | 掃き掛け | swept boshi |

| Ichimai Boshi | 一枚帽子 | the whole boshi is tempered |

| Jizo Boshi | 地蔵帽子 | boshi pattern resembling the head of jizo |

| Kaen | 火焔 | flame shaped boshi |

| Kaeri | 返り | turnback (refers to the boshi at the mune) |

| Kaeri yoru | 返り寄 | leaning kaeri the turnback in the boshi dips towards the ha |

| Kissaki | 切先 | point of blade |

| Ko-maru Agari | 小丸上が | the tip of the ko-maru boshi is near the point of the blade |

| Ko-maru Sagari | 小丸下が | the tip of the ko-maru boshi is well away from point of the blade |

| Midare Komi | 乱込み | uneven pattern in boshi |

| Mishina Boshi | 三品帽子 | boshi with hakikake and a slight tarumi (slack) in the ha side |

| O-kissaki | 大切先 | large kissaki |

| Saki agari | 先上がり | the tip of the boshi is near the point of the blade |

| saki | 先幅 | blade width at yokote |

| Saki sagari | 先下がり | the tip of the boshi is well away from point of the blade |

| Togari | 尖り | pointed also refers to the shape of the boshi |

| Yakisaeru | 焼き下げる | the tip of the boshi is down from the kissaki or the return on the boshi moves down the mune |

| Yakizume | 焼詰 | boshi line with no turnback |

Horimono 彫物

| Romanji | Kanji | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Bohi | 棒樋 | wide shaped groove |

| Bonji | 梵字 | sanskrit characters |

| Dokko | 独鈷 | single prong vagra |

| Fudo Myoo | 不道明王 | Buddhist wisdom king, one of Jusanbutsu |

| Futasujibi | 二筋樋 | two grooves side by side |

| Gomabashi | 護摩箸 | grooves which look like a pair of chopsticks |

| Hachiman Daibutsu | 八幡大菩薩 | God of War |

| Hi | 樋 | grooves carved in sword |

| Hoju | 宝珠 | Buddhist magic jewel |

| Kurikara | 倶利伽羅 | sword or ken with dragon wrapped around it |

| Naginata hi | 薙刀樋 | naginata grooves on all types of swords |

| Rendai | 蓮台 | carving representing lotus |

| Ryu | 竜 | dragon carving |

| Sankoken, Sanko Tsuken,Sankozuka | 三鈷剣 | engraving of a sword with buddhist vajra handle |

| Soe-bi | 添樋 | thin hi carving typically under a bo-hi |

| Shin no Kurikara | 真の倶利伽羅 | style of carving is the most life-like dragon |

| Tsume, kozumi | 爪 | claw handle at the end of a sword |

| Vajra | 金剛 | Buddhist tool and favored weapon of King of Tenbu |

Nakago 茎

| Romanji | Kanji | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ATO MEI | 後銘 | signature added at a later date |

| CHUMON MEI | 注文銘 | name of the person who placed an order for a sword to be made |

| FUNAGATA | 舟形 | ship bottom shaped nakago |

| GAKUMEI | 額銘 | original signature inlaid after being cut-off or sword shortened |

| GASSAKU | 合作 | something made jointly by two or more people |

| GIMEI | 偽名 | false signature |

| GISAKU | 偽作 | item intentionally made as a counterfeit |

| HA AGARI | 刃上がり | type of nakago end slants up (agari) towards the ha |

| HAMUNE | 刃棟 | the edge of the nakago on the ha side, unlikely to have rust re-applied in the event of tampering with the nakago |

| HIDARITE SAGARI | 左手下がり | yasurime slanting down to the left |

| HIGAKI | 檜垣 | cross hatched pattern throughout the yasurime |

| HORI DO SAKU | 彫同作 | horimono was made by the same person that made the sword |

| HORI DO TSUKURU | 彫同造 | horimono was made by the same person that made the sword |

| HORI MEI | 彫銘 | mei of the person who made the horimono |

| JUNIN MEI | 住人銘 | signature meaning “resident of “ |

| KAKINAGASHI HI | 掻き流し樋 | groove which goes past the machi, but do not extend to the nakagojiri |

| KAKITOSHI HI | 掻き通し樋 | groove which extends all the way to the nakagojiri, and is open at the end |

| KAKUBARI | 角張り | when referring to the saki of a nakago, it means that the sides are not tapered, |

| KANI BOTAN | 蟹牡丹 | crab peony, which is a flower sometimes found engraved on nakago |

| KATTE AGARI | 勝手上がり | yasurime slanting up the right |

| KATTE SAGARI | 勝手下がり | yasurime slanting down to the right |

| KENGYO | 剣形 | triangular or pointed nakago |

| KESHO YASURIME | 化粧鑢目 | decorative file marks on nakago |

| KIJIMOMO | 雉股 o | pheasant’s thigh shaped nakago |

| KINAIBORI | 記内彫 | engraving done for echizen yasutugu |

| KINZOGAN | 金象嵌 | gold inlay appraisal mei by the honma family are in kinzogan |

| KIRI | 切り | horizontal file marks or nakago cut, straight across |

| KIRITSUKE MEI | 切付銘 | a mei which replaces the mei when the nakago is osuriage, and in effect, the person who signs as having done the shortening is certifying that it was the original mei |

| KURIJIRI | 栗尻 | rounded nakago jiri |

| MACHI | 区、匸、 | division between the nakago and the blade itself, |

| MACHI OKURI | 関送り | machi has been redone and moved up slightly |

| MEI | 銘 | swordsmith’s signature |

| MEKUGI | 目釘 | sword peg |

| MEKUGI ANA | 目釘穴 | hole for mekugi |

| MUMEI | 無銘 | no signature (unsigned blade) |

| NAGAMEI | 長銘 | long mei |

| NAKAGO | 茎 | tang of the blade |

| NAKAGO JIRI | 茎尻 | the end or but of the nakago |

| NAKAGOJIRI | 茎尻 | tang end |

| OMOTE | 表 | signature side of the nakago |

| ORIKAESHI MEI | 折り返し銘 | mei in which the original nakago is cut and folded back |

| OSHIGATA | 押形 | rubbing of the signature on the nakago |

| O-SUJIKAI | 大筋違い | yasurime which is at a steep angle to the nakago |

| SAKIBARI | 先張 | nakago it means that the sides are not tapered |

| SENSUKI | 詮鋤 | yasurime that is parallel to longitudinal axis |

| SHINOBI ANA | 忍び孔 | an extra mekugi ana, place near the tip of the nakago |

| SHIPPARI | 尻張 | nakago – it means that the sides are not tapered |

| SHUMEI | 朱銘 | red lacquer signature |

| SOEMEI | 添銘 | additional mei or inscription |

| SOSHOMEI | 草書銘 | mei in grass writing very difficult to read without special studies |

| SOTOBA GATA | 卒塔婆形 | a nakago shape which resembles the sotoba, or grave marker |

| SUJIGAI | 筋違い | yasurime which is at angle to the nakago literally, “different lines “ |

| O SURIAGE | 大磨上 | nakago is cut short – no signature |

| SURIAGE | 磨上 | shortened tang |

| SURIAGE MEI | 磨上銘 | signature of the smith who shortened the sword |

| TACHI MEI | 太刀銘 | signature facing away from body when worn edge down |

| TAKANOHA | 鷹の羽 | hawk’s feather yasurime lines slant downwards to both sides from the centerline or shinogi of the nakago |

| TAMESHIMEI | 試銘 | cutting test mei |

| TANAGO BARA | たなご腹 | fish belly shaped nakago |

| TENSHO SURIAGE | 天正磨上 | swords that were shortened in the tensho period ( 1573 ) typically done for early daimyo |

| UBU | 生 | original, complete, unaltered tang (nakago) |

| UMA HA | 馬歯 | horse teeth hamon |

| URA | 裏 | side of the nakago facing toward the body |

| URA MEI | 裏銘 | mei on the ura of the nakago |

| URA NENKI | 裏年記 | date inscription on the ura, or back, of the nakago |

| YASURIME | 鑢目 | file marks |

| YODOMI | 淀み | two holes drilled from both sides to make the mekugi ana |

| ZAIMEI | 在銘 | has a mei, the opposite of mumei |

| ZOKUMEI | 俗名 | a name of the smith in addition to his regularly used name |

Other

| Romanji | Kanji | Description |

|---|---|---|

| O- | 大 | large |

| AGARI | 上がり | rise or go up |

| AIKUCHI | 合口 | a tanto with no tsuba |

| ASAI | 浅い | shallow |

| ATARI | 当たり | correct kantai |

| BU | 分 | japanese measurement (approx .1 inch) |

| BUKE | 武家 | samurai, warrior families |

| CHAKUSHI | 嫡子 | heir |

| CHOJI OIL | 丁子油 | clove oil for the care of swords |

| CHOKOKUSHI | 彫刻師 | an engraver same as horimonoshi |

| CHU | 中 | medium |

| CHUMON-UCHI | 注文打ち | items made to order |

| DAI | 大 | great or large |

| DAIMEI | 代銘 | signed by a pupil or son |

| DAIMYO | 大名 | feudal lord |

| DAISAKU | 代作 | made by a pupil in the name of his master |

| DAISHO | 大小 | a matched pair of long and short swords |

| DAITSUKE | 代附 | price assigned by honami ke in the early tokugawa period |

| DEN | 伝 | school |

| DENRAI | 伝来 | Family ownership ( typically Daimyo familiy provenance) |

| DOHAI | 同輩 | contemporary seen gohai and senpai |

| DOZEN | 同然 | smiths who are contemporary and similar, used in Kantei |

| GENDAITO | 現代刀 | traditionally forged sword blades by modern smiths |

| GO | 号 | professional name of smith |

| GOHAI | 後輩 | junior classman |

| GOKADEN | 五ヶ伝 | the five schools of the koto period |

| GOKORO | 心 | a hint of whatever precedes the term |

| GOTO | 豪刀 | katana of around three shaku in length |

| GYAKU | 逆 | reverse |

| GYOBUTSU TOHAKU MEITO OSHIGATA | 行物東博名刀押形 | oshigata of famous swords of the imperial properties of the tokyo museum |

| HABAKI | はばき | blade collar |

| HANDACHI | 半太刀 | tachi mountings used on a katana or wakizashi |

| HARAMIRYU | 孕竜 | dragon wrapped around a sword with its body away from the sword |

| HITSU ANA | 櫃穴 | openings in tsuba for kozuka or kogai |

| HON | 本 | book |

| HONBAMONO | 本場物 | real or original |

| HONMONO | 本物 | genuine |

| HORIMONO | 彫物 | carvings on sword blades |

| HORIMONOSHI | 彫物師 | carving specialist, engraver |

| ICHIMON | 一門 | mon, or school, in japanese |

| JINAN | 次男 | second son |

| JUYO TOKEN | 重要刀剣 | juyo sword |

| JUYO | 重要 | very important work |

| JUYO BIJITSUHIN | 重要美術品証書 | an old level of quality judged by the japanese government defining the sword or kodogu as important cultural assets replaced with juyo bunkazai |

| JUYO BUNKAZAI | 重要文化財 | new government designation after juyo bijituhin |

| KAISHO | 楷書 | printing style of writing, in which kanji are easily recognized |

| KAISHOMEI | 楷書銘 | mei in square style writing, approaching printing in appearance |

| KAJI | 鍛冶 | swordsmith |

| KAKIHAN | 書き判 | swordsmiths or tsuba makers monogram |

| KANJI | 漢字 | japanese characters |

| KANTEI | 鑑定 | studying a sword, and making a decision as to its provenance |

| KANTEIKA | 鑑定家 | one who judges, or does the “kantei” of swords |

| KAO | 花押 | a special type of signature, used like a seal |

| KARAKUSA | 唐草 | arabesque |

| KEBORI | 毛彫 | engraving using very fine lines ke means hair |

| KEI | 系 | system or line can refer to familial line or guild line |

| KEISOHEI | 軽装兵 | lightly equipped soldiers, light infantry |

| KENMAKIRYU | 剣巻竜 | 剣巻竜 dragon wrapped around a sword see kurikara |

| KENSAKU | 羂索 A | buddhist terminology, the means of capturing and taming evils rope |

| KERAI | 家来 | retainer, vassal |

| KINDAI | 近代 | recent times, |

| KIRI AJI OR KIRIMI | 切味 | feeling of sharpness |

| KIRI KOMI | 切り込み | sword cut or nick on the blade from another sword |

| KIZU | 傷 | flaw |

| KO- | 古 | in this translation, denotes early the kanji means old |

| KO- | 小 | small |

| KO-BIZEN | 古備前 | early bizen |

| KODAI | 後代 | later generation |

| KODOGU | 小道具 | all the sword fittings except the tsuba |

| KOGAI | 笄 | hair pick accessory |

| KOIGUCHI | 鯉口 | the mouth of the scabbard or its fitting |

| KOJIRI | こじり | end of the scabbard |

| KOKUJI | 刻字 | kanji carved in the blade |

| KOMEIKAN | 古銘鑑 | abbreviation for the name of a book on swordsmiths, or possibly, refers to old meikans in general |

| KOSAKU | 古作 | made in the koto period |

| KOSHIRAE | 拵え | sword mountings or fittings |

| KOTO | 古刀 | old sword period (prior to about 1596) |

| KOTO MEIJIN TAIZEN | 古刀銘尽大全 | complete list of koto signatures, sometimes abbreviated as taizen, also read as koto meizukushi taizen |

| KOZUKA | 小柄 | handle of accessory knife |

| KUDARIRYU | 下り竜 | dragon going down the sword in other words, the head of the dragon is towards the machi |

| KUNI | 国 or | province |

| KURIKARA | 倶利伽羅 | dragon and sword also called kenmakiryu 剣巻竜 meaning dragon wrapped around a sword |

| KUSA KURIKARA | 草倶利伽羅 | arabesque style of kurihara horimono see karakusa also read as so no kurikara |

| KYOGOKAJI | 京五鍛冶 | five principle kaji of kyoto |

| MEIBUN | 銘文 | the inscription in the mei in total, as opposed to just individual kanji |

| MEIGIRISHI | 銘切り師 | people who specialized in inscribing mei |

| MEIJI | 明治 | meiji period (1868-1912) |

| MEIKAN | 銘鑑 | list of people or artisan with book |

| MEITO | 名刀 | famous swords |

| MON | 門 | formal school , physical location |

| MON | 紋 | family crest |

| MONJI | 文字 | kanji engravings on the blade which are in the ordinary type of script, rather than the bonji 梵字, which are specific religious characters |

| NADO | 等 or | this means and so on, etc |

| NANAKO | 魚子 | raised dimpling (fish roe) |

| NANBAN | 南蛮 | southern barbarians, the europeans |

| NANBOKUCHO | 南北朝時代 | period 1323-1394 |

| NANCHO | 南朝 | southern dynasty during the nanbokucho |

| NENDAI | 年代 | age, epoch, period |

| NENGO | 年号 | era name |

| NENKI | 年記 | date inscription |

| NENREI | 年齢 | age of tsuba or fittings |

| NIHONBI | 二本樋 | double grooves |

| NIJI | 二字 | two kanji |

| NINKANMEI | 任官銘 | official such as kami, daijo, etc |

| NOBI | 延び | extended- usually describing kissaki |

| NYUSATSU | 入札 | kantei bid |

| OITE | 於いて | at ( as in made at this place ) |

| RIN | 厘 | 厘 one tenth of a bu 2 bu 3 rin may sometimes be written as 2 3 bu |

| RYU | 竜 | dragon |

| RYUHA | 流派 | school |

| SAGEO | 下緒 | cord used for tying the saya to the obi |

| SAME | 鮫 | ray skin for tsuka |

| SAMURAI | 侍 ( alt士 ) | japanese warrior or the warrior class |

| SASHI OMOTE | 指表 | the side facing out when the sword is worn ha up, as with a katana, katana mei |

| SASHI URA | 指裏 | the side facing in when the sword is worn ha up, as with a katana, tachi mei |

| SAYA | 鞘 | sword scabbard |

| SAYAGAKI | 鞘書 | attribution on a plain wood scabbard |

| SAYAGUCHI | 鞘口 | mouth of the scabbard (koi) |

| SENGOKU JIDAI | 戦国時代 | warring states period in japanese history specifically, 1490-1600 |

| SENPAI | 先輩 | a term which can mean upperclassman |

| SEPPA | 切羽 | washers or spacers |

| SHAKU | 尺 | a unit of measure, which is slightly less than 1 foot |

| SHIMAME | 縞目 | stripes |

| SHIN SHINTO | 新新刀 | new ( new eriod starting after shinto during meiji restoration ) |

| SHINMEI | 真銘 | genuine mei also called shoshinmei 正真銘 |

| SHINTO | 新刀 | new sword period (1596 to 1781) tokugawa period where smiths tried to recreate old school artist appearance of kamakura and nambokucho |

| SHIRASAYA | 白鞘 | plain wood storage scabbard |

| SHODAI | 初代 | first generation |

| SHOGUN | 将軍 | supreme military leader |

| SO NO KURIKARA | 草の倶利伽羅 | dragon wrapped around a sword, carved in arabesque |

| SUN | 寸 | a unit of measure, which is about 1.2 inches 10 sun equals 1 shaku, which is about 1 foot |

| TABAGATANA | 束刀 | mass produced swords |

| TAGANE | 鏨 | punch or chisel |

| TAGANE KIZAMI | 鏨刻み | mark made with a chisel or punch |

| TAGANE MAKURA | 鏨枕 | the metal which is raised around a punch mark |

| TOKENSHO | 刀剣書 | books on japanese swords |

| TOSHO | 刀匠 | master swordsmith |

| TSUBA | 鍔 | sword guard |

| TSUKA | 柄 | sword handle |

| TSUKARE | 疲れ | meaning that this sword is tired |

| UCHIKO | 打ち粉 | fine powder used to clean sword blades |

Jidai 時代 or other date terminology referenced in origami

| Jidai | 時代 | Period |

| Heian | 平安 | 794 to 1185 |

| Kamakura | 鎌倉 | 1185–1333 |

| Nanbokucho | 南北朝 | 1333 to 1392 |

| Muromachi | 室町 | 1392 to 1573 |

| Sengoku | 戦国 | 1465 to 1615 |

| Momoyama | 桃山 | 1568 to 1600 |

| Edo | 江戸 | 1603 and 1868 |

| Bakumatsu | 幕末 | 1853 to 1867 |

| Meiji | 明治 | 1868 to 1912 |

| Taisho | 大正 | 1912 to 1926 |

| Showa | 昭和 | 1926 to 1989 |

| Heisei | 平成 | 1989 to 2019 |

| Reiwa | 令和 | 2019 to present |

| Shoki | 初期 | (the beginning of period) |

| Zenki | 前期 | (the first part of period) |

| Chuki | 中期 | (the middle of period) |

| Atoki | 後期 | (late part of period) |

| Sueki | 末期 | (the end of period) |